伊曼努爾·列維納斯

伊曼努爾·列維納斯

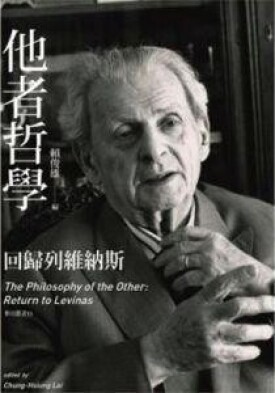

伊曼努爾·列維納斯(Emmanuel Levinas,1906年1月12日—1995年12月25日),法國著名哲學家。出生於立陶宛考納斯。通過融通思考希臘文化和希伯來文化,通過對傳統認識論和存在論的批判,他為西方哲學提供了思考異質、差異、他性的重要路徑,從而揭示了從倫理的維度重建形而上學的可能性。同時也是是20世紀歐洲最偉大的倫理學家,他最為徹底地反對自古希臘以來的整個西方哲學傳統,並在此基礎上提出了最激進的真正意義上的“他者”理論,成為當下幾乎所有激進思潮的一個主要的理論資源。

列維納斯幼年在立陶宛接受過傳統的猶太教育。二戰後,師從神秘的猶太導師舒沙泥,研習《塔木德》(猶太教法典)。直到生命的後期列維納斯才承認舒沙泥對其學術影響的重要性。

伊曼努爾·列維納斯

刊發於紐約時報的列維納斯訃告提到,他對自己付之於海德格爾的熱情表示遺憾,因為後者與納粹關係緊密。甚至在一次公開的演講中列維納斯提到,人們應該以寬恕之心對待德國人所犯下的罪行,但海德格爾不應被寬恕。

博士畢業后,列維納斯到巴黎的一所私立猶太中學,後進入高等教育體系。他先於1961年在普瓦提埃大學教書,後於1973年來到索邦大學,直到1979年退休。他也是瑞士弗萊堡大學的兼職教授,並於1989年榮獲巴爾扎恩哲學獎。

列維納斯於50年代進入法國知識分子的思想前沿,他的觀念基於“它者的規範”或按他自己的話講“規範為哲學第一本位”。對於列維納斯來講,它者是不可知的,並且無法凝練出基於自我的客觀規律,因為這隻會囿於傳統的形而上學觀念(這被列看做是本體存在論)。他更傾向於把哲學看作是“愛的智慧”而非傳統希臘語中的“智慧之愛”。這樣,規範成為獨立於主觀的實體,成為凌駕於主體的民族責任;繼而這種責任超越了客體對真實之探索的意義本身。

列維納斯在一生中曾遭遇了納粹帶來的不幸,見證了西方世界在二十世紀所經歷過的幾乎所有暴力。這些以奧斯維辛大屠殺作為頂峰的歷史暴力滲透在他的問題與思考中,以至於對他,就像阿多諾所說的,哲學的根基不再是驚奇,而是恐怖。列維納斯追問理性是如何同野蠻結合在一起的,並勇於提出要反對海德格爾式的哲學氣候(沒有倫理的“存在”),以及反對希臘哲學傳統中“中性”化的哲學概念對於倫理所具有的優先性。他認為對於哲學,還有一項偉大的工作需要完成,即“以希臘語言來講述希臘文化所不知的道理”,因此終其一生,他都在探索如何在仍然用理性的方式來思考的同時,給哲學的內在注入另一種“生氣”:給予這說著古希臘語言的哲學來自希伯來的氣息,在這不可磨滅的歷史恥辱的記憶深處,喚醒那同樣是不可磨滅的上帝的“蹤跡”。雖然列維納斯和阿多諾一樣,為了走出這恐怖而承擔起了批判“本真性行話”的思想使命,但是,與阿多諾所設想的“無人的烏托邦”不同,列維納斯思考的是一個使愛鄰人成為可能的“人的烏托邦”。列維納斯一反時代潮流地堅持思考主體和人道主義的可能性,這或許是一條更具批判性、更尖銳,但也更為積極的道路。

《從存在到存在者》

《和胡塞爾、海德格爾一起發現存在》

伊曼努爾·列維納斯

《別樣於存在或超越本質》

《倫理與無限》

《時間與他者》

1.楊大春等主編:《列維納斯的世紀或他者的命運》(“杭州列維納斯國際學術研討會”論文集),中國人民大學出版社,2008.

簡介:該論文集彙集了美國、英國、法國、比利時、以色利等國外著名列維納斯研究專家及國內該領域幾乎所有的著名學者的研究成果,代表了列維納斯研究的最高、最全面的成就,對於掌握列維納斯豐富多樣的思想以及他與兩希傳統複雜關係具有非常重要的參考價值。

2.王恆著,《時間性:自身與他者》,江蘇人民出版社,2008.

簡介:《時間性——自身與他者(從胡塞爾海德格爾到列維納斯)》是國內第一本對作為現象學家的列維納斯的哲學思想的追溯性研究著作。其主要觀點是:時間問題是現象學思想傳統中一以貫之的根本,胡塞爾的時間意識就是主體性本身,海德格爾認為時間性就是存在的境域,而對於列維納斯,正是在時間中才有真正的他者出現,或者說與他者的關係才真正有時間的呈現。時間之謎,就是主體之謎,就是他者之謎,列維納斯正是基於時間,才另立了“作為他者的主體”這一後現代倫理之要義。《時間性——自身與他者(從胡塞爾海德格爾到列維納斯)》適合於德國和法國哲學、後現代思潮、倫理學等方面的研究者和有興趣者。

Introducing Levinas to Undergraduate Philosophers

Anthony F. Beavers

The question of the source of the moral "ought" is no small question, nor is it

unimportant. Our own philosophical tradition has dealt with the question in several

ways producing a variety of answers. Some of these include locating the "ought" in

the structure of reason (Kant), in the human being's desire for pleasure

(Utilitarianism), or in the will of God (Aquinas). The reason why the question is so

important is because different conceptions of the source of the moral ought

ultimately give rise to different conceptions of what is right and wrong; they also

affect the way we answer the biggest of all ethical questions, why be good.

Levinas begins his answer to this question precisely with the origin of the moral

ought, which unfolds on the level of the individual. For him, ethics is, first and

foremost, born on the concrete level of person to person contact. He does not find

the moral "ought" inscribed within the laws of the cosmos, in reason, or in any

universal desire for pleasure. Instead, each individual case of moral conflict

produces the moral "ought" itself.

Today I wish to do nothing more than present an exposition of the source of

the "ought" in Levinas. It will be difficult to present an argument here,

because the moral "ought" for Levinas has already occurred before reason comes on

the scene. To present a rational argument for what occurs before reason is

impossible; to do so would be to take reason into a domain where reason cannot go,

in this case, to the point of contact between one person and another. Thus, Levinas

can only have for us an evocative appeal. The goal of presenting ethics in this

fashion is not to discover the truth of ethics, but to make an appeal for ethical

transFORMation. Levinas invites us to listen, not only to what he has to say, but,

more importantly, to the voice of the Other, who sanctions all of our moral

obligation.

To get this lecture off the ground, I will derive Levinas' moral "ought" by starting

with an assumption: ethics occurs always in relation to other persons. When asked

how to define ethics, I am assuming that our answer will include an important

reference to other people. This is not necessarily to say that there can be no

ethics without at least two people -- though this is the case for Levinas. It is to

say that ethics is an important issue for us because it governs the way in which we

relate with one another. This assumption is not unfounded: indeed, St. Thomas tells

us that "harm should not be given to an other". Kant's Categorical Imperative

indicates that the moral agent should "treat humanity, whether in his/her own person

or the person of another, not only as a means but also as an end in itself." And

Mill's "principle of utility" implies others when he notes that ethics is rooted in

the notion of the greatest happiness for the greatest number. If ethics is concerned

with the other, then it would appear that in order to fill out a complete account of

ethics, the means by which two people come in contact with each other will be

vitally important. Here, then is the root of Levinas' concern: to establish the

source of contact between persons or the source of interpersonal meaning, and in

finding this meaning, Levinas finds the ethical.

To a non-philosopher, the source of contact between persons seems to be a

superficial question. The answer is, at first, easy. The other person is met in

experience everyday, on the street, in the classroom, in the workplace, etc. To a

philosopher, however, the question is not so easy: we in the tradition recognize the

difficulties inherent in interpersonal contact. Does the other person have a mind?

Is the other a creation of my imagination, as Descartes asks looking out of his

study at the automata that pass by dressed in coats and hats? In light of these

questions, though, we can never truly deny the existence of the other in the context

of the street, the classroom, or the workplace, even if we can deny such contact in

a theoretical context. It is on the level of life, then, as opposed to that of

theory, that Levinas has his appeal.

Levinas comes directly out of the tradition established by Descartes, Kant and

Husserl. "Every idea is a work of the mind," writes Descartes in his Meditations.

Ideas are created, invented by a mind, not discovered. This leaves Descartes

with a problem: "How can [ideas] that have their origin in the mind nevertheless

give us knowledge of independently real substances." He answers this question

through proofs for God's existence and divine veracity. But as the tradition

progresses, Kant notes that God cannot be used within philosophy to the extent that

Descartes would like. Thus, Descartes is left alone in his world with only his

ideas: there is no contact with an other who is not an other in one of his ideas.

Husserl takes this to its logical consequences in the fifth of his Cartesian

Meditations and notes that the other is "there," present to me, but only in the

sense that the other has for me. He writes, "Consciousness makes present a 'there

too', which nevertheless is not itself there and can never become an 'itself-

there'." The other of Husserl's Cartesian Meditations is not an extra-mental

other, that is, one who exists independently of me; rather, the other is only the

meaning that I constitute for the other. In other words, the meaning of being an

other comes down to my interpretation of the other, an interpretation which is the

working of my own mind quite apart from what or whether the other may be.

If we can accept this notion that ideas are inventions of the mind, that ideas are,

when it comes down to it, only interpretations of something, and if ethics, in fact,

is taken to refer to real other persons who exist apart from my interpretations,

then we are up against a problem: there is no way in which ideas, on the current

model, refer to independently existing other persons, and as such, ideas cannot be

used to found an ethics. There can be no pure practical reason until after contact

with the other is established.

Given this view towards ideas, then, anytime I take the person in my idea to be the

real person, I have closed off contact with the real person; I have cut off the

connection with the other that is necessary if ethics is to refer to real other

people. This is a central violence to the other that denies the other his/her own

autonomy. Levinas calls this violence "totalization" and it occurs whenever I limit

the other to a set of rational categories, be they racial, sexual, or otherwise.

Indeed, it occurs whenever I already know what the other is about before the other

has spoken. Totalization is a denial of the other's difference, the denial of the

otherness of the other. That is, it is the inscription of the other in the same. If

ethics presupposes the real other person, then such totalization will, in itself, be

unethical.

If reducing the other to my sphere of ideas cuts off contact with the other, then we

are presupposing that contact with the other has already been established. And if

contact with the other cannot be established through ideas, then we must look

elsewhere. Thus, Levinas looks not to reason, but to sensibility, to find the real

other person.

Sensibility, for Levinas, goes back to a point before thought originates, before the

ordering of a world into a system or totality. Sensibility is passive, not

active as thought is, and it is characterized primarily by enjoyment. Life as it is

lived, (rather than understood), is lived as the satisfaction of being "filled" with

sensations, the satisfaction of feeding on the environment.

Departing from Heidegger who maintains that we live from things through their

function as tools and implements, Levinas maintains that we live from these things

as nourishments. I eat my bread; in the activity of eating it becomes a part of my

body. I bathe in the music of Beethoven's "Moonlight Sonata"; in the activity of

bathing. I "digest" the music. It becomes me. This "living from" is a matter of

consumption, a matter of taking what is other and making it become a part of me.

Levinas writes:

Nourishment, as a means of invigoration, is the transmutation of the other into the

same, which is the essence of enjoyment; an energy that is other, recognized as

other, recognized ... as sustaining the very act that is directed upon it becomes,

in enjoyment, my own energy, my strength, me.

This taking on of what nourishes me conveys a separation between me and what has yet

to nourish me. "Enjoyment is made," writes Levinas, "of the memory of its thirst; it

is a quenching." Enjoyment then includes the memory of once not having been

satisfied with what now satisfies me. Thus, enjoyment also involves stepping back

from my environment; "living from ... delineates independence itself, the

independence of enjoyment and happiness ..." Before enjoyment, there is me and

the other thing that has yet to nourish me, even if the otherness of what will

nourish me becomes apparent only in enjoyment, in the "memory" of its thirst. I can

represent the bread, but this will not feed me. I must eat it. But then in eating my

bread, the memory of hunger, evinces a separation between the bread and me. Thus, in

enjoyment, the self emerges already as the subject of its need.

If Levinas is correct, then, the human being starts first as happy, satisfied with

the plenum of sensations. He/she enjoys them. This enjoyment as independence is the

initial FORMation of the I. But, this self, the self of enjoyment, constitutes an

egoism. It is happy, but selfish. The self of enjoyment journeys into the world to

make everything other part of itself, and it succeeds very well at this task. Cohen

summarizes all of this nicely:

[Sensation] is called "happiness" because at this level of sensibility the subject

is entirely self-satisfied, self-complacement [sic], content, sufficient. Instead of

[rational] synthesis, there are vibrations; instead of unifications, there are

excitations; rather than an ecstatic self, there are margins of intensities,

scattered stupidities, involutions without centers -- egoism and solitude without

substantial unity; a sensational happiness ... This event does not happen to

subjectivity, this eventfulness, this flux, is subjectivity.

Thus, Levinas finds on the level of sensibility a subjectivity that is more

primordial than rational subjectivity. It is not limited by the sphere of one's

own ideas, but by the egoist self that goes out to enjoy the world. What is

important here is that, unlike the sphere of ideas, sensibility reaches further out

into the domain of the extra-mental.

Having established subjectivity on the level of sensibility provides Levinas with a

place "where" the other can be met, not in the cabinet of consciousness, but on the

street, in the classroom, or in the workplace, where the egoism of enjoyment has the

possibility of becoming "filled" with sensations. Furthermore, establishing

subjectivity on the level of sensibility leads Levinas to a point where he can

establish that the human subject is, first and foremost, passive. Sensations come to

me from the outside only to be swallowed up on the inside. But, unlike the contents

of ideas, sensations are discovered, given. They are not invented.

The ethical moment, the moment in which the moral "ought" shows itself, is found,

for Levinas, on the level of sensibility when the egoist self comes across something

that it wants to enjoy, something that it wants to make a part of itself, but

cannot. That which the self wants to enjoy but cannot is the other person. The

reason that it cannot enjoy the other person is not rooted in some deficiency of

sensibility, but in the other person who pushes back, as it were, who does not allow

him/herself to be consumed in the egoism of my enjoyment. The other resists

consumption. The presence of the other, on this level, is not, properly speaking,

known. The other person is encountered as a felt weight against me.

Thus, for Levinas, the other has some power over me. Indeed, the other is a

transcendence that comes from beyond the categories of my thought, from beyond the

world, from the other side of Being. Because of the other-worldliness of the

epiphany of the other in the face-to-face, the face speaks thus: "I am not yours to

be enjoyed: I am absolutely other," or to put the claim in Levinas' terms, "thou

shalt not kill."

John Burke describes the initial approach of the other person in terms of

astonishment or surprise. In so doing, he also notes the essential element of

radical passivity that arises from contact with the other person. He writes, "My

astonishment seems less an activity of mine, a willful projection of a function of

my interests, than the deepest mode of passivity." Vulnerability arises from

such a surprise, a being caught off guard by the epiphany of the other person. My

solitude is invaded by the other person who comes from nowhere.

This element of "catching off-guard" is important here, because it indicates more

about the presence of the other than the mere perception of the other. This catching

off-guard makes me aware of the presence of the other as an other who is due my

concern, not because I choose to give it to the other, but because it is demanded of

me. I want to consume the other, but cannot. Several steps are involved in

elucidating this moment. In this discussion, I will present two of them: proximity

and substitution. These two notions will lead us to an understanding of ethical

responsibility in Levinas, though it must be understood that responsibility is not

derived from these steps; it is, rather, bound up with them.

The face of the other, that element of the other that is the ground of interpersonal

contact, indicates an immediacy with the other person that Levinas

calls "proximity." Proximity is felt as immediate contact. Levinas writes:

... the proximity of the Other is not simply close to me in space, or close like a

parent, but he approaches me essentially insofar as I feel myself -- insofar as I

am -- responsible for him. It is a structure that in nowise resembles the

intentional relation which in knowledge attaches us to the object -- to no matter

what object, be it a human object. Proximity does not revert to this intentionality;

in particular it does not revert to the fact that the other is known to me.

The proximity of the other demands a response; thus, Levinas claims that proximity

is responsibility, or the ability to respond. Proximity must then be thought of

as a weight upon me that comes from the outside. But unlike Sartre who finds an

antagonism in this entry of the other from the outside, Levinas finds the

possibility of ethics, or the ground upon which ethics first shows itself. Not only

does the possibility of ethics show itself here, the self now takes on a different

characteristic. A new subjectivity is born that indicates that my self, as a

subject, is a primary projection towards the other as a move of responsibility to

the other. The very meaning of being a social subject is to be for-the-other.

Levinas writes, "Subjectivity is being a hostage." In other words, subjectivity

arises from confrontation with the other person where the other is dominant, never

reducible to the domain of the same. Subjectivity means, in this context, subjection

to the other.

The self is a sub-jectum: it is under the weight of the universe ... the unity of

the universe is not what my gaze embraces in its unity of apperception, but what is

incumbent upon me from all sides, regards me, is my affair.

The self is subjected to the other who comes from on high to intrude upon my

solitude and interrupt my egoist enjoyment. The self, feeling the exterior in the

guise of the other pass through its world, is already obligated to respond to the

transcendent other who holds the self hostage. In turn, this means that "the latent

birth of the subject occurs in obligation where no commitment was made." I do

not agree to live ethically with the other at first, I am ordered to do so. The

meaning of my being a self is found in opposition to the other, as an essential

ability to respond to the other. I am, above all things, a social self indentured a

priori, made to stand in the place of the other.

This standing in the place of the other provides Levinas with one of his most

powerful concepts, "substitution." Substitution arises directly from the self as

held hostage by the other. It is the means by which my being responds to the other

before I know that it does. Indeed, substitution is a sign of how other-directed the

human being actually is. In comporting myself towards the other person in

substitution, my identity becomes concrete. "In substitution my being that belongs

to me and not to another is undone, and it is through substitution that I am

not 'another,' but me."

If Levinas is correct here, the meaning of being a social subject is primarily to be

for the other person. Again, substitution is indicative of a sacrifice of self -- it

cannot be merely the idea of being in the place of the other person, for ideas have

yet to come on the scene. As Lingis suggests:

One is held to bear the burden of others: the substitution is a passive effect,

which one does not succeed in converting into an active initiative or into one's own

virtue.

While it is true that Levinas is vague on the essence of substitution, the

suggestion seems to be that in being persecuted by an other person, I am made to

consider the person as an other. However, since such consideration cannot be made on

the conceptual level, this consideration becomes manifest in a comportment of the

self to the other person. Consideration for the other means being-considerate-for-

the-other. Substitution then is recognizing myself in the place of the other, not

with the force of a conceptual recognition, but in the sense of finding myself in

the place of the other as a hostage for the other. Substitution is the conversion of

my being as a subjection by the other into a subjection for the other.

To get a sense of how powerful Levinas' notion of substitution is, let me depart

from the vocabulary of his language for a moment and cast the discussion into

concrete terms. Suppose for a moment that you are walking down the street and the

person in front of you pushes a garbage can into the street. You might pick up the

garbage can, you might not -- but, certainly you will not feel like an injustice has

been done to the garbage can. Now suppose that in the same situation, the person in

front of you pushes another person into the street. Suppose further that this

person, while lying on the ground looks up at you. Do you "feel" the need to

respond? Levinas says that at this moment, the ethical command has been waged. You

are obligated to respond. If the desire to respond does not, at first, present

itself as a command, and you respond because you want to respond, then you have just

been witness to the depth that substitution has taken in your own being. The desire

to respond is already a responsiveness to the command of the other.

Some ethicists find that if we respond to the person because we feel a personal need

to do so, then we are really satisfying our own desire, and, as such, our action

does not have true moral worth. Levinas' point is more profound on this score. He

notes that there is a metaphysical explanation for why we have this desire to

respond. The explanation is rooted, once again, in substitution. First of all, the

person has a transcendence that the garbage can does not have, and secondly, we

have, in fact, already substituted ourselves for the other. Within Levinas'

framework, the desire to help the other emerges because I am held hostage by the

other to the core of my being, and, in substitution, I am made to stand for the

other, before freedom and reason comes on the scene.

This brings us, at last, to Levinas' notion of ethical "responsibility." This notion

of responsibility, much in line with our concept of responsiveness, means that in

being a subject I am already in the grip of the Other. It also entails that all

thought enters on the scene after the epiphany of the other in the face-to-face.

This is to say that the other person precedes my ethical subjectivity, and that

ethics precedes any conceptual science. Inasmuch as responsibility is foundational

for all interpersonal relationships, it is in responsibility that we are going to

find a means to pass from an encounter with the real other person into ethics.

Levinas writes:

In [Otherwise than Being] I speak of responsibility as the essential, primary and

fundamental mode of subjectivity. For I describe subjectivity in ethical terms.

Ethics, here, does not supplement a preceding existential base [as Heidegger would

have it]; the very node of the subjective is knotted in ethics understood as

responsibility.

Furthermore, "the tie with the Other is knotted only as responsibility" as

well. Thus, responsibility is the link between the subject and the other person, or,

in more general terms, the source of the moral "ought" and the appearance of the

other person as person and not as thing are one and the same. There is no authentic

sociality apart from ethics, and there is no ethics apart from sociality. To say

that responsibility is foundational for ethics and interpersonal relations is to say

then not only that responsibility is what relates one subject to another, but it is

to go on to say that the meaning of the otherness of the other person is given in

responsibility, and not in my interpretation of the other person. The very meaning

of being an other person is "the one to whom I am responsible." Thus, the contact

with the real other person that I spoke of at the beginning of this lecture as

something presupposed by the very meaning of ethics turns out to be, in Levinas'

account, the source of the moral "ought."

Anthony F. Beavers

The University of Evansville

1. The process presented in this lecture follows the lines established in Totality

and Infinity. Between the writing of this text and the later text, Otherwise than

Being or Beyond Essence, Levinas changed his mind on the ordering of the process.

See Lingis' introduction to Otherwise than Being for more inFORMation on this point.

2. The Philosophical Works of Descartes, eds. Elizabeth S. Haldane and G. R. T.

Ross, vol. II, Meditations (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 162.

3. Robert Paul Wolff, Kant's Theory of Mental Activity: A Commentary on the

Transcendental Analytic of the "Critique of Pure Reason" (Gloucester, Mass: Peter

Smith, 1973), 32.

4. Edmund Husserl, Cartesian Meditations: An Introduction to Pure Phenomenology,

translated by Dorion Cairns (Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1960), 50, 139.

5. The "world" for Levinas is always the world constituted in subjectivity. It

should not, therefore, be taken as extra-mental.

6. Levinas, Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority, translated by Alphonso

Lingis (Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1969), 111.

7. Levinas, Totality and Infinity, 113.

8. Levinas, Totality and Infinity, 110.

9. Richard Cohen, "Emmanuel Levinas: Happiness is a Sensational Time," Philosophy

Today 25 (1981): 201. This excellent article shows Levinas' debt to Husserl's

phenomenology and his departure from it.

10. There are at least three different types of subjectivity in Levinas: 1) rational

subjectivity -- the self of representation that occurs in the "I think"; 2)

subjectivity of being -- the self of enjoyment and need; and 3) ethical

subjectivity -- the social self that arises from transcendent interpersonal contact.

11. Levinas, Totality and Infinity, 109. "If cognition in the FORM of the

objectifying act does not seem to us to be at the level of the metaphysical

relation, this is not because the exteriority contemplated as an object, the theme,

would withdraw from the subject as fast as the abstractions proceed; on the

contrary, it does not withdraw far enough."

12. John Patrick Burke, "The Ethical Significance of the Face," ACPA Proceedings 56

(1982): 198.

13. See Burke, "The Ethical Significance of the Face," 198. The reason that the

other "comes from nowhere" is seen in the fact that the "world" for Levinas is

constituted by my reason and exists "for me." The Other comes from beyond the world,

hence, from a domain that is not able to be located by me.

14. Levinas makes a distinction between desire and need. Need differs from desire to

the extent that a need can be satisfied while a desire cannot. Thus, desire has a

metaphysical significance. Put concretely, I desire the other person, but since the

other cannot be reduced to the domain of the same, my desire for the other can never

be fulfilled.

15. See Andrew Tallon, "Intentionality, Intersubjectivity, and the Between: Buber

and Levinas on Affectivity and the Dialogical Principle," Thought 53 (1978):

304. "The radical passivity of Levinas's self ... emerges only with the advent of

the other, with the face of the other drawing near me; This nearness (proximité) is,

of course, not an intentionality by me or him alone, not a mental "state" or

activity, but meaning between us."

16. Emmanuel Levinas, Ethics and Infinity: Conversations with Phillipe Nemo,

translated by Richard Cohen (Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1985), 97. This

elegant little book goes a long way in making Levinas' thought approachable to the

uninitiated.

17. See Emmanuel Levinas, Otherwise than Being or Beyond Essence, translated by

Alphonso Lingis (Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1981), 139: roximity,

difference which is non-indifference, is responsibility."

18. Levinas, Otherwise than Being, 127.

19. Levinas, Otherwise than Being, 127.

20. Levinas, Otherwise than Being, 140.

21. Levinas, Otherwise than Being, 127.

22. Alphonso Lingis in the translator's introduction to Otherwise than Being, xxxi.

This introduction consists of a concise exposition of Levinas' thought in this work.

23. I wish to thank Carl Weisner for helping me to develop this point.

24. Levinas, Ethics and Infinity, 95.

25. Levinas, Ethics and Infinity, 97.